Tampa-based Mining Company Seeks Protection from Water Quality Assurance Act

TAMPA — There was a time, a dozen years ago, when you couldn’t turn on a TV in Florida without seeing an ad for the Mosaic Co. You’d see scenes of golden waves of grain and farmers tilling their crops, and you’d hear a woman talking in glowing terms about the world’s largest phosphate miner.

“Our promise is to always take our commitment to the environment seriously,” the ads would say.

The process of mining phosphate unearths a certain amount of radiation. That’s what led the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to decree that the waste from phosphate mining and processing would have to be stacked up in gigantic mounds, to protect everybody who’s not in the phosphate business.

The land where the mining once occurred tends to remain radioactive. An estimated 50,000 Floridians now live atop what used to be mining pits.

“The owners think the property is safe, but it’s not — it’s hazardous,” said Glenn Compton of the environmental group ManaSota-88. “It poses a serious health risk for people.”

Now some of those people are suing Mosaic for unsafe radiation levels. “The ground and soil that support and form the very foundation upon which [the plaintiffs’] homes sit is contaminated with uranium and radium-226 caused by Mosaic’s phosphate mining operations,” one lawsuit says.

Mosaic appears concerned they’re going to lose — so concerned, in fact, that the Fortune 500 company has turned to the Legislature for help. Debate in the Florida House on a bill to to shield the company from lawsuits under the Water Quality Assurance Act is set to begin today, January 15.

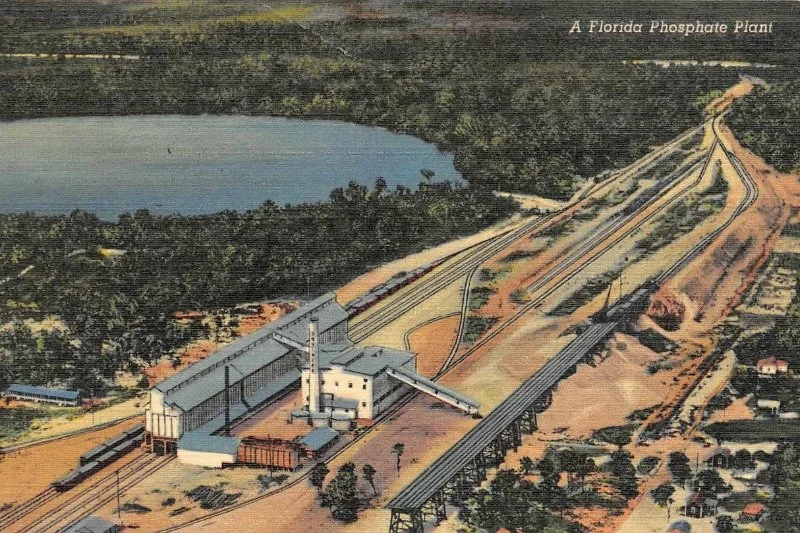

Ever since 1899, when ex-Confederate soldier Albertus Vogt discovered the original phosphate deposit while digging a well near Dunnellon, people have been digging the stuff up and converting it into fertilizer. Phosphate mining now extends through 450,000 acres of Central Florida. Most of the mines are owned by Mosaic, based in Tampa.

In 2017, residents of Lakeland’s Oakbridge and Grasslands communities sued the developer who built their homes on top of old mining sites.

They reached a confidential settlement in 2024, but, in announcing the deal, their law firm pointed out that “testing before development of the subdivisions showed radiation levels 11 to 21 times higher than the acceptable risk limit.”

Yet the company never warned homebuyers of the danger.

In 2020, residents of two more Mulberry communities, Angler’s Green and Paradise Lakes, filed suit against Mosaic, hoping to hold the company liable for any health damage to the homeowners.

“Exposure to levels of radiation similar to those identified in the Angler’s Green and Paradise Lakes communities,” the suit contends, “translates to residents receiving over one chest X-ray per week — with obviously no diagnostic or health purpose whatsoever.”

Piney Point and other disasters

Phosphate mining has had a huge economic impact on Florida. It also has had a disastrous impact on its ecosystems.

For instance, in 1997 a dam full of acidic water atop a gypsum stack at a Mulberry Phosphates fertilizer plant broke during heavy rains. It spilled 56 million gallons of acidic wastewater into the Alafia River, killing every living thing in the 42 miles between Mulberry and Tampa Bay. The company declared bankruptcy.

Or look at the Piney Point disaster five years ago, which resulted from state regulators repeatedly bending the rules to accommodate the mining industry.

Mosaic has played a major role in more than one of these environmental disasters.

In 2004, for example, Tropical Storm Frances broke the dam atop a gypsum stack at Mosaic’s Riverview plant. Some 65 million gallons of waste flowed into a creek flowing into Tampa Bay, killing fish, mangroves, and seagrass.

The company generates a lot of pollution to dump, so in 2012 it got a state permit to suck 70 million gallons of water out of the aquifer every day. Mosaic uses the water to dilute its waste before spewing it into various waterways. The permit allowed Mosaic to tap more than 250 wells in Hillsborough, Manatee, Polk, Hardee, and DeSoto counties, an area that since 1992 had been under tight water-use restrictions.

In 2015, the company reached a $2 billion settlement with the EPA over its handling of hazardous waste in both Florida and Louisiana. A government spokesman called it “the most significant enforcement action in the mining and mineral processing arena” in the U.S.

Piney Point and those other disasters did not lead legislators to impose any new rules or regulations on the industry. On the contrary, lawmakers are now considering easing up safe water regulations on phosphate giants like Mosaic.

Mosaic and the Florida Legsislature

“Mosaic is one of the largest campaign contributors in Florida politics,” Justin Garcia reported recently. “Records show the company has donated more than $500,000 to state candidates and committees through the first nine months [of 2025] — including more than $100,000 to a fundraising committee led by GOP leaders in the Florida Senate.”

Three years ago, Dover Rep. Lawrence McClure, a Republican who’s a partner in an environmental consulting firm, successfully pushed through a bill Mosaic wanted. The bill would let the mining giant test its phosphogypsum waste as road-building material instead of continuing to stack it up in giant mounds. After the bill passed, Mosaic paid $100,000 to sponsor a fundraiser for McClure’s political action committee, Conservative Florida.

When the Tampa Bay Times broke the story on this, McClure contended the fundraiser was not a payback for doing Mosaic’s bidding. He insisted it was nothing more than standard practice. Still, McClure was so grateful to Mosaic that he’s one of two sponsors on this bill to protect the company from being sued.

“Our Legislature shouldn’t be looking out for them,” said Ragan Whitlock of the Center for Biological Diversity. “They should be looking out for Floridians.”

The Water Quality Assurance Act

Here’s what Mosaic needs to be saved from: a 1983 law called the Water Quality Assurance Act.

“The law imposes something known as ‘strict liability’ on companies that release pollution into the ground or water,” Garcia reported.

That means “they can be forced to compensate people impacted by that pollution regardless of whether the release was accidental or the result of corporate carelessness. The idea is to ensure companies handling materials that can sicken or kill people and wildlife have maximum financial incentive to be as careful as possible.”

The bill that Mosaic wrote, and that McClure is co-sponsoring with Rep. Richard Gentry, R-Astor, would undercut that standard. Instead, notes Garcia, “it would no longer be enough to just prove that Mosaic is responsible for the elevated radiation levels. A plaintiff would also have to prove that Mosaic was somehow negligent, too. That’s a much higher bar to have to clear in court.”

In order to avoid lawsuits, the bill says, the phosphate company would have to record a legal notice that the land is a former mine. Then it would have to call in the state Department of Health to conduct a radiation survey. You, as a buyer, might not know about either of these.

McClure told WUSF-FM that the existing law is unfair to Mosaic. He said it’s wrong to hold the company liable for endangering everyone’s health just because “once upon a time, a machine unearthed some rock.”

By passing this bill, he said, “we’re going to have more data as a function of this than we currently do today.”

Whitlock scoffed at that argument for letting Mosaic off the hook.

“This is still very much a handout to the phosphate companies to reduce their liability,” Whitlock told me. “The breadcrumbs they have provided in return change nothing.”

Lawsuits Threaten Real Estate Deals

Mosaic execs have been trying since at least 2024 to get the Legislature to protect them from lawsuits under the Water Quality Assurance Act. So far, their efforts have fallen short.

Why have they been so intent on passing this? Because, Garcia wrote of the 2025 effort, “Mosaic framed the legislation as the key to unlocking real-estate development in one of the most rural parts of Florida.”

Phosphate is a finite resource. Mines don’t last forever. The company is looking ahead to its future.

It learned the lesson of the St. Joe Co., a Panhandle pulp and paper giant that eventually realized it needed a new product. St. Joe closed its paper mill and switched to developing and selling its extensive real estate holdings (with help from the taxpayers).

Mosaic itself, in a handout to legislators last year, told them that “many lands that once supported phosphate mining have untapped potential due to legal uncertainty that limits reuse. By providing liability protections for the sale of previously mined phosphate lands, this legislation removes barriers to repurposing them for new opportunities.”

Now they’re back to try it one more time. The Florida House has already held two committee meetings on HB 167. Both of the hearings occurred last year, before the session began this week.

I watched a video of the Judiciary Committee meeting from last November. This bill was the only item on the agenda. The discussion took less than 10 minutes, and then every member of the committee voted yes. Holding the two committee votes before the start of session means the bill is teed up for fast passage this week. Then it will head to the Senate, where Senate President Ben Albritton is already on board.

~ ~ ~

This article was written by Craig Pittman and originally published in the Florida Phoenix. It has been edited for length and style.